Shaky man in the gym 2: Keep on shakin’

For part 1, see here.

july 2009

Neil has an article about PD and exercise (PDF) published on the Parkinson’s NSW website.

october 2009

Dear Krista

Look at this, from the Fall 2009 Newsletter of the venerable Parkinson’s Disease Foundation.

http://www.pdf.org/en/fall09_exercise_parkinsons

Yes, it’s the intensity that is critical.

This is the opposite to the “take it easy and don’t tire yourself” adage that remains the conventional message put out by professionals to those living with Parkinson’s disease.

While reading Dr Petzinger’s article I had a brain flash back to a lecture theatre at Sydney University in the 1960s when a professor of Australian History remarked, “Although we say that So-and-So were the first to ‘discover’ such-and-such place, it was often the case that So-and-So were the official party dispatched by the authorities. When they’d arrive at such-and-such place, they’d often find that common people had long discovered the place and had settled there.”

november 2009

Mistress Krista

I need to row an extra 10 metres, 574 metres to 584 metres, in two minutes to recapture the lead (Men’s 55yrs – 64yrs) in the Two Minute Rowing Challenge at the gym I attend.

Neil tackling the rowing

The event is a time trial held between Monday 2 Nov and Saturday 14 Nov.

I had my first and so far only attempt last Monday 9 Nov, rowing 574 metres and displacing another competitor on 571 metres. Other men were a long way behind.

Tonight (Wednesday 11 Nov), a fellow who I see training mainly on the treadmill at a steep incline achieved 583 metres. (He’s 58 years old.) With his aerobic capacity, he’d probably stroke faster over the rear end of the race than I do. My rate seemed to start out at 38/min, fading to 34/min at the end. Resistance was at max.

Contestants may have as many attempts as they wish between 2 and 14 Nov.

I feel lured to give it another go.

Have to improve my distance by 1.57% to tie.

Another way of looking at it is that I’ll need to be about 1.9 seconds ahead of where I reached at 2 minutes on Monday.

In terms of strokes, it seems I only need to increase the number of strokes by between 1 and 2 across the entire event.

I usually have gym sessions on Mon, Wed, Fri. nights and Sat or Sun afternoon for around 55 minutes a session. Am tempted to have another go tomorrow, Thurs night, leaving an opportunity to try again on Sat.

We old fellas are pretty fierce competitors. Our distances and times stand up well against the mainstream of men in the younger categories.

There’s also an event in which contestants have to perform as many rounds of (7 pushups, 7 situps, 7 squats) in five minutes. I had a go to-night. My main difficulty is standing up. Also am very slow in rolling over from pushup to situp. (Was allowed to place my toes under a treadmill when doing situps; people with PD usually cannot sit up.) My score was poor. Thankfully no-one else in the 55yrs – 64 yrs men’s slot has contested this event so far.

One good idea in preparing for another attempt at the rower would be to increase my sleep. It’s now 12.45am, not unusual for me. Sometimes I’m back in the office around 4am.

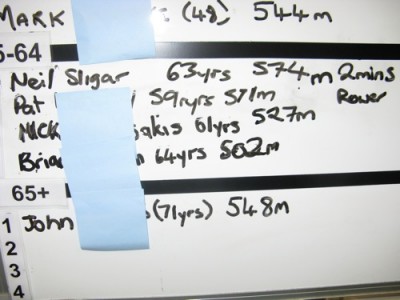

Pics of my rowing last Monday and of competitors’ names/performances on the white board as at Monday are attached. (I asked that surnames be covered.) Others have competed; there’s only space for the leading four.

Scoreboard

I have a hard row to hoe!

Best wishes

Neil

Nov 22

Dear Krista,

Over the past fortnight I’ve competed in Aquafit gym’s 2 minutes rowing challenge. Also competed in a pushup/situp/squat event in which competitors had to perform as many “rounds” as possible within 5 minutes. Each round comprised 7 pushups, 7 situps, and 7 squats.

Unfortunately I was the only competitor in the latter in the Men’s 55 years – 64 years category. My performance was relatively dreadful; my problem wasn’t in speed of pushup, situp or squat, but in standing up. Only completed 7 rounds.

Movements that are simple, perhaps automatic, to most people become projects for those with Parkinson’s.

No excuses in the case of the rowing challenge. The top three competitors were a long way ahead of the rest. I was pipped into second place by a younger and fitter man. He rowed 583 metres in 2 minutes; I rowed 577 metres at my third attempt. (My first attempt was 574 metres.) In a second attempt, my backside slipped out of the seat around one minute into the row when ahead of my first attempt. By the third attempt I felt tired and lethargic. It surprised me that it was my best performance.

Competing gives purpose to my training and allows comparison of my efforts with those of other men. It’s also a relief not to be typecast by Parkinson’s. There’s no “PD” placed after my name on the whiteboard in the list of competitors. There’s no-one telling me to “rest if you feel tired.”

Times or distances achieved in gym events are screwed tighter and become new short to medium term targets.

My exercise goals range from broad statements:

- Retain good general health, especially in relation to heart, blood pressure, and blood chemistry;

- Develop and maintain a strong musculature to assist in retaining normal posture;

- Continue improving: to short-term and medium-term measurable targets.

The first two broad statements, about retaining good general health and maintaining a strong musculature, have stood since I set them in 2000.

Program sheets set out specific exercises and sets, reps, time or weight to be achieved at each gym visit. They are shaped by the short to medium term targets.

It seems that I can’t peak in aerobic and strength components at the same time. My lifting performances have fallen while preparing for the rowing challenge, so regaining that loss is my first task.

Bring on a weightlifting competition.

The vigour of my exercise regime would be regarded as lunacy by many in the Parkinson’s community but there’s a hint of change.

Petzinger and others at the University of Southern California have concluded that exercise benefits for those living with Parkinson’s are positively related to intensity of that exercise. (Stumptuous could have told them that.)

As medication wanes, my tremor becomes conspicuous. Shoppers last week asked if I needed help. While stretching at the gym, a concerned fellow member enquired if I was O.K. At the railway station the ticket seller became alarmed I was having a fit and followed me on to the platform, offering a glass of water. An hour and a half after medication such awful signs dissipate.

I don’t feel an impact of Parkinson’s on bike or rower but it certainly affects my running. Maybe walking/running are more complex movements than we think. In weightlifting, Parkinson’s detracts significantly from my “explosive” capacity such as in snapping a weighted bar to my shoulders. That still leaves many lifts with minimal “explosive” component.

My personal experience has been that someone with Parkinson’s disease, through hard training, can far exceed the aerobic and strength performance of the average Joe or Sally. I’d reject any notion of having superior athletic talents. My current aerobic and weightlifting output is the consequence of around 1,600 gym sessions during almost all of which I’ve close to busted my guts.

Professional advice, generally applied, to people with Parkinson’s along the lines of “don’t tire yourself and don’t lift heavy weights” in my opinion is both wrong and potentially harmful if Parkinson’s is the only reason for such a remark. Naturally, those embarking on hard aerobic training should be sure they have no other health problems.

If hard training has harmed me then I’m yet to detect it. It brings temporary relief from tremor and rigidity and sleep comes more readily. Maybe I’m unique. Maybe others have had detrimental effects from vigorous exercise. I’ve not read the evidence.

At least I don’t suffer a common fourth symptom of Parkinson’s disease, toppling over. Physiotherapists at Sydney University are considering this tendency and its relation to leg strength. They will be further assessing me in the coming week, having already placed within a group unlikely to fall.

Many of my peers, on diagnosis with Parkinson’s, hasten to gain a disabled car parking sticker enabling use of car parking spaces close to shops, railway stations, and the like. Some join exercise groups specifically designed for those with a disability.

Doing so may be the right approach for them. I’ll take the contrary approach. If reduced stamina threatens, I’ll increase the strain of my aerobic routine. If reduced strength threatens, I’ll put more plates on the bar.

When commencing my exercise regime in 2000 I speculated that maintaining a strong body might delay the stooped posture typical of Parkinson’s. So far so good. Neither do I experience freezing of movement experienced by many of my peers. Nor do I have a shuffling gait although its whispers are apparent on the treadmill or when walking up a steep slope.

Eventually, Parkinson’s disease will probably win. Movement will be close to impossible, I may no longer be able to eat, no longer able to speak, I may be confined to a wheel chair.

But I’m not keen to be there.

Best wishes

Neil

january 2010

An excerpt from an article that Neil sent me:

After controlling for several potential confounders, lower extremity muscle weakness accounted for 10% of the variability on a standardized test of BMD [bone mineral density]. This is noteworthy, since muscle strengthening or exercise are not interventions clinicians would consider when treating a patient with Parkinson’s disease (PD). In fact, early practice guidelines on physiotherapy (PT) for PD overlooked muscle as a potential target for exercise intervention, targeting instead the cardinal signs and symptoms of the disease with therapies that were often not supported by published research.

This practice continues today in many clinical settings. [Research that] showed a clear association between upper and lower body muscle weakness and hemi-Parkinson’s disease in 1987 and stated that “muscle weakness appears to be a primary symptom of Parkinson’s disease which may relate to disturbed motor programming due to basal ganglia dysfunction”… was largely ignored by the clinical community, perhaps because [this] statement challenged conventional thought or because it was thought that declines in muscle strength were a part of the normal ageing process.

Increasing muscle strength through resistance training might improve BMD, mobility and reduce the occurrence of falls and hip fractures. In order to increase strength, the intensity of exercise would, presumably, have to be suitably high…

Current thoughts on PD rehabilitation reflect a much more dynamic interplay between the rehabilitation environment, behavior, brain and rehabilitative outcomes in people with PD. Indeed, high intensity, task complexity, saliency, novelty and other factors may be necessary to promote struttural and metabolic plasticity in the brain and musculoskeletal systems of persons with PD; however, to date, studies are still forthcoming and no agreed exercise guidelines exist.

Until recently, intense exercise was feared to worsen the symptoms of PD by perhaps increasing the underlying muscle tone, and so, for these individuals, high intensity exercise was to be avoided. These beliefs still dominate PD rehabilitation research and clinical practice today. Few dare to challenge these “truths”, current leading texts on management of PD with exercise still reinforce the notion that high-intensity resistance training has “minimal effects on the symptoms” such as postural reflex impairment, and, as a result, relatively little progress has been made in the treatment of these patients.

It will be interesting to see if future studies reinforce the stereotype that people with so-called chronic neurodegenerative conditions such as PD cannot improve under any circumstances or if it is we who cannot advance our own beliefs.

Hirsch, Mark. Muscle Strength in Parkinson’s Disease: Commentary on Pang and Mak. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 291–292

As Neil writes, “In summary, despite evidence as far back as the 1980s that weight-bearing exercise and intensity of exercise are positively related to relief of the symptoms of PD, medical professionals have chosen to ignore such evidence and have continued to promote unfounded “truths” that people living with PD should avoid strenuous activity. (Probably the main reason doctors don’t prescribe non-pharmacological treatment is their lack of training in same.)

The promising sign is that there’s a tiny cluster of professionals exploring intense exercise and announcing their findings.”

june 2010

Fans of Shaky Man will enjoy his latest adventure: his first film! He speaks about his diagnosis and the role of vigorous exercise — including weight training.

What an incredible, brave man. Neil keeps it real.

By the way, that “105” bench press he mentions… Neil is talking about kilos.

october 2010

Dear Krista,

Lines written spontaneously on arriving home from a rowing challenge.

“Bradykinesia means slowness of movement and is one of the cardinal manifestations of Parkinson’s disease.”So say Beradelli et al in that great bedtime read, Pathophysiology of bradykinesia in Parkinson’s disease

Well, Beradelli old sport. You’d best rethink bradykinesia. Cos I’m just home from the gym, having competed in the two minute rowing challenge against a cluster of aged warriors recalling their glorious past and battling with a fierce determination threatening heart attack.

And I’m coming second in the 55yrs – 64yrs category. A young lad of 55 years (I’m 64yrs) rowed 596m compared with my 570m. Another youngster is tied with me on 570m but I take precedence by age.

And I was diagnosed with the shaky condition over twelve years ago.

Chris, a real rower (on the water), eloquently summed up my effort “All grunt. Shithouse* technique.” (Sorry, mum. I shouldn’t have even repeated such coarse language.)

Competitors have a few days left to post a better distance. The fellow tied with me will surely try. So will I.

My distance to-night was 7 metres less than my performance twelve months ago. But given my difficulties sleeping recently, I’m satisfied to have finished. Maybe I’ll improve on Sunday. And there’s still the pushups/situps/squats event in which to line up.

Best wishes

Neil

* Spell check says “consider revising.”

december 2010

Dear Krista

What’s changed in the life of Shakyman during 2010?

- My “on” periods (periods during which my medication is effective) have reduced. Appointment times at which I meet clients (yes…am still working) are dictated by when medication is most likely to be functioning. Whether my medication is on or off has never influenced training times.

- Erratic sleep has become “normal” and surely must impact on at least the aerobic component of my training regime. I’m guilty here; during 2010 my neurologist has recommended a 9pm medication dosage but, more often than not, I don’t take it. I don’t excuse this and am attempting to be more disciplined.

- Maximum lifts have declined.

- I hadn’t considered until recently the negative impact of some medication on physical performance. Let me tell you.

Until late November 2010 I’d been mystified as to why my heart rate had been peaking around mid 130s this year rather than 150s as in previous years. (My usual at rest bpm = around 60). Laziness or fatigue was suspected but I felt as much exertion was being put in as previously.

I mentioned my lower peak heart bpm to my pharmacist. “That’s the XXX” replied the pharmacist, naming a medication I’ve been taking since May this year.

“It subdues heart rate and is on the banned list for sports such as shooting. It wouldn’t help in your case, of course.” (He was referring to my rowing and bike riding in which my body wants as much oxygen as possible.) My neurologist confirmed that the medication is “exercise intolerant”.

This news put my recent fourth place in an indoor rowing competition into a new light.

I’d been despondent about coming fourth in the 55 years and over category, even though only seven metres separated 2nd to 4th in an event testing how far we could row in 2 minutes. My distance was 570 metres, compared with 577 metres in the same event twelve months ago. I felt exhausted after the first minute and battled to keep going.

This, my worst effort, may have been my best. I was dragging a dirty great pharmaceutical anchor.

Lesson learnt? Take into account impact of medication. With my neurologist’s concurrence, XXX has been ditched. A few nights ago my heart rate reached 152 bpm after a burst of three minutes at 35 kms/hr during interval training on the bike.

Relief from Parkinson’s symptoms, physical and mental, comes for me with sweaty, gut-busting exercise sessions, each of around fifty-five minutes, four times a week. Sessions comprise stretching, around fifteen minutes of interval training on stationary bike or indoor rower, and around thirty minutes of weight lifting.

Parkinson’s is called a movement disorder but I’m most free of the condition when moving at max. There are many other symptoms that don’t take a holiday. You’ll gain a picture of what it’s like to live Parkinson’s by viewing the following YouTube produced for the Swedish Parkinson’s Association.

My training isn’t sculpted by Parkinson’s. It’s always been directed at my general health.

Shortcomings in individual exercises that may be Parkinson’s–related are addressed but, as a whole, I work out for my total wellbeing.

Parkinson’s appears to have little impact on my capacity for intense physical activity.

As I increase intensity the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease dissipate. In my home and office, I’m significantly impaired by tremor and rigidity. (See my YouTube of June 2010.) At slow speed on the bike, my riding is rough. As the pace increases, movement becomes more fluent.

I compete at a large gym in bike and rower contests with “normal,” physically fit men. Parkinson’s is briefly left behind.

Automaton-type movements such as pedalling or pulling oars feel unimpeded compared with walking, which seems a more complicated movement. I enter rowing and cycling contests but wouldn’t enter a running contest.

In 2008 I competed in an Iron Man event. No problems with the 2 km ride nor the 500 m row nor the 20 x 3 push-ups nor the 20 x 3 sit-ups nor the 20 x 3 unweighted squats. But the 500 m run was a matter of survival.

Weightlifting is where my training most starkly diverges from conventional advice. When strengthening is mentioned on websites concerning exercise for people with Parkinson’s, advice is most commonly along the following lines.

National Center on Physical Activity and Disability

For me, Exercise = Flexibility + Aerobic + Strength.

I lift “heavy” weights (i.e. near 1 rep maximum) without harm. I’ve not been injured in almost eleven years of gym activity.

There’ve been episodes of soreness, particularly in my right (Parkinson’s side) deltoid and shoulder. The remedy is obvious: Ease off on lifts that cause soreness until the soreness has gone. My experience has been that soreness is more likely to follow high repetitions of low weights than vice versa.

My lifting routine is simple.

- Try to work every area of my body at each session.

- Never repeat the same lifts at the next session.

- Give priority to lifts that stress the most muscles.

- Keep sets of any one lift to 1 and reps to maximum of 6.

- Usually lift to 90% of maximum.

The specifics can be read in my previous postings in Stumptuous.

Parkinson’s disease is apparent in my lack of explosive strength. I believe the correct label for this is “power”, being strength x velocity. Slowness in initiating movement is a symptom of Parkinson’s and is obvious in me when trying to snap a bar to my shoulders.

An oddity is that even though my “snappy” strength is greatly affected, my top speed is probably little, if at all, affected. In a previous Stumptuous posting I mentioned hitting a pedalling top rpm of 140. My competition results would indicate that, compared with other men of my age, speed isn’t lacking although initiating speed may be compromised.

Research by physiotherapists at Sydney University appears to reflect my experience.

Summarising. My exercise regime is:

- For general health rather than being tailored as Parkinson’s therapy.

- Comprised of three components flexibility, aerobic, strength

- Performed at close to my maximum exertion.

- Focused at performance targets which, when achieved, are extended a little further. Performances are measured.

- Controlled by me. (I respect and consider other’s opinions but I’m in charge.)

I describe but don’t advocate my exercise routine. What others do is for them to determine. Anyone contemplating intense physical activity should firstly have medical confirmation that it’s safe to do so.

My creed remains that my exercise regime will be the same as that of anyone else working out for general health. It will be performed to my hardest. If Parkinson’s brings impediments, then I’ll work around them. It won’t dictate how I train.

In my November 2009 Stumptuous commentary I cited research revealing the benefits of intense exercise for people living with Parkinson’s. Dr Becky Farley, who was associated with the USC research mentioned by me, initiated exercise programs in 2009 for those living with Parkinson’s. Forcing participants beyond their comfort zone appears to be a fundamental element.

On 11 January 2011 I’ll click over to 65 years of age. My height is 179cms (5ft 10.5 inches) Weight is 87kgs (192lbs). I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1998. My training occurs at Aquafit Fitness and Leisure Centre, Campbelltown. NSW Australia.

Best wishes

And Happy Christmas

Neil