Abdominal training

Seems like the abs are the big focus for infomercial fitness products these days. The latest one I saw was a little gizmo that you strapped on to your tummy. It would vibrate your abs so that they turned into a rippling granite mountain range.

Perhaps, dear readers, you have stronger intestinal resistance than I, but I imagine that several minutes of forcible ab vibration would result in me talking to Ralph on the porcelain phone.

And then I always wonder: what if those ab gadgets actually did work? What do you do if the rest of you is all squashy and out of shape? I envision a strange hybrid person with a tiny bumpy midsection, and large amorphous everything-else, like a cross between a wasp and a jellyfish.

Anyhoo, let’s just get this out of the way right now: most of those ab products are crap, and the only thing they’ll whittle down is your wallet.

So, assuming that we all want abs that will make Brad Pitt look like Homer Simpson, how to go about it? Maybe it’s best to eliminate two nasty myths immediately.

myth #1: You can spot reduce the abdominal region by doing situps or crunches.

There is no such thing as spot reduction, no matter how badly we all want it to be true. You will not “tone” your abs by doing crunches. Waist size is determined by bodyfat levels, which depend on your diet, activity level, and hormones.

Grrls who put on fat through the midsection (and menopausal/perimenopausal women whose fat deposition patterns have shifted to midsection) will have a hard time getting lean enough to see their abs, while women who put on fat primarily in the lower body can often see abs, especially upper abs, at relatively higher levels of bodyfat.

Women who have had multiple pregnancies, or abdominal surgery such as a C-section or abdominal hysterectomy, may notice some laxity in the ab region, or some separation down the centre, as a result of trauma to the tissues. To some degree this is correctable through sensible training, but there’s a good chance that the area which had the incision will not regain its original condition. You can strengthen them pretty well, though.

However, in general, if you want to see your abs and/or lose inches from your waist, you must lose bodyfat. No quick fixes, sorry. Aw, don’t cry. You knew it was too good to be true! Here, have a Kleenex. Blowing your nose will give you some ab work.

myth #2: You shouldn’t use weight for abdominal training because that makes abs bulky.

Abs are like any other skeletal muscle and require resistance. What we call the abs is a thin sheet of muscle, about the thickness of a magazine (and not the Vogue fall fashion issue either).

Given their shape, abs have very limited capacity for hypertrophy (size increase) compared to muscles like the quadriceps. Women especially are unable to exhibit hypertrophy to any great degree, due to much lower testosterone levels than men (I know, I keep harping on this, but people don’t seem to get it). Yes, competitive male bodybuilders often get that weird bloated gut with bumpy abs on top, which makes it look like the guys have swallowed a tortoise. It’s not from using weight for their ab exercises; it’s from excessive drug use. So breathe easy. Unless, of course, you’re also injecting growth hormone.

Personally I think it’s awesome that I don’t have to do crunches till my hair goes gray in order to get good, strong abs. I was the kid in gym class who’d fake an asthma attack to get out of the situp test. God, I hated situps SO MUCH! There’d always be some snotty little natural jock who could crank out a hundred of them without messing up a single shiny hair, and then there’d be me, lying on the floor, wondering if it was possible to die from an ab cramp.

These days my abs are one of my best body parts, and I do only a few sets of them, maybe 10 reps a set, 1 to 3 times a week. Using resistance, and treating abs like any other muscle, has given me a whole new lease on life. Or at least on my childhood situp trauma.

what do the abs do?

What we think of as the abs, the rectus abdominis, is only one part of a dynamic system of muscles which support the torso. The muscles are designed to work as a versatile unit which is both stable and mobile. It can go rigid to support a heavy squat bar, but it can also twist and bend in various directions. It’s a pretty nifty model of engineering, really.

What we think of as the abs, the rectus abdominis, is only one part of a dynamic system of muscles which support the torso. The muscles are designed to work as a versatile unit which is both stable and mobile. It can go rigid to support a heavy squat bar, but it can also twist and bend in various directions. It’s a pretty nifty model of engineering, really.

The rectus abdominis, as I mentioned, is a flat sheet of muscle which runs from the ribcage to the pelvis and is attached at various points along the way. It’s the attachments that make the characteristic “bumps” we associate with ab muscles. Different people have differently shaped abs. Some people’s ab attachments are symmetrical; others’ aren’t. Some people’s abs are narrow; others’ are wide. There’s some variety there, and much of your ab definition (or not) and shape is going to be genetic.

The abs have two main functions.

- As prime movers, they bring the ribcage towards the pelvis and vice versa.

- As stabilizers, they contract isometrically with the other torso muscles to provide a rigid column (uh huh huh, I said rigid column) of support. This is why powerlifters sometimes say that the best ab exercises are heavy squatting and deadlifting, and why strong abs can also be part of a good rehab program for lower back pain.

To feel this condition of rigid stability, make the following comparison. While you’re sitting reading this, give your tummy a poke. It probably feels more or less squishy since it’s relatively relaxed. Now, exhale forcefully and then don’t inhale. Put your hand on your tummy and feel around, noting the way your abs have hardened. Now don’t inhale till I tell you to.

*whistling aimlessly, looking absentmindedly off in the distance*

Oh, are you still waiting? Sorry about that, heheh, I guess I wasn’t paying attention. Ooh, that blue colour is not a good one for you.

how can i get a bodacious belly?

If all you want is strong abs, follow the instructions below. If you want strong and visible abs, you’ll have to work on losing bodyfat too, so get thee to the dieting 101 article.

First thing to remember, as I said, is that abs need to be trained with resistance, like any other muscle. This means you can feel smug about doing only a few sets of abs a week, while other people are killing themselves with hundreds of crunches a day, and your results are likely to be better. Ha ha ha!

|

|

|

It’s worth reviewing the form of the basic crunch for starters, since this is the exercise that most people are familiar with. Crunches were the alternative to situps, which everyone said were bad because you recruited your hip flexors for the top part of the movement.

Personally I think people worry way too much about isolating the abs. Yes, it’s good to do a movement properly, and hit what you want, and yes, there can be good reasons for isolation work, but it’s also worth remembering that the body is designed to work as a system. Don’t get too hung up on singling out one part, because the ab bone is connected to the hip bone, dig. Someone like a runner may benefit from hip flexor work.

Anyway, so, to do a regular crunch, lie on a mat or folded towel or plushy carpet (whatever you have available to keep your spine from grinding into the floor). You can bend your knees and rest feet on floor, you can support lower legs on a bench, you can hold legs up straight, you can straighten one leg and bend the other, it’s up to you. Hand position is also optional. You can reach out in front of you, you can cross your arms over your chest, you can hold them behind your head.

The way I prefer to do it is to clasp hands behind head, making sure elbows are flared out to the side (people like to cheat by dragging their head up with their arms). Begin the movement by doing a pelvic tilt (all y’all should remember those suckers from the Jane Fonda days). A pelvic tilt is done by trying to bring the pelvis toward the ribcage, and pressing the bellybutton down into the spine. Try a few just to get the hang of it.

OK, once you’ve got your pelvic tilt thang going, hold it there and curl the upper body up. As you come up, look up at the ceiling, not forward between your knees. At the top of the movement, pause for a moment, then slowly uncurl.

Take your time to execute this movement in the beginning. Shut your eyes if you like, to feel what’s happening in your midsection (besides that chili dog leaping around your duodenum). It’s useful to gain awareness of what this movement feels like, so that when executing other movements you have some control.

To increase the resistance on regular crunches, hold a plate behind your head or on your chest. I find it more comfortable to sort of cradle my head on the plate. Look up at the ceiling and come up slowly, focusing on driving your bellybutton down into your spine. You can increase the range of motion by placing a small rolled up towel under your lower back.

You can adapt this exercise to be done slowly with a weight plate in your hands. Hold the plate with straight arms above you, and crunch up slowly, moving the upper body as one unit. To increase difficulty, move your hands farther behind your head. Crunches can also be made more challenging by performing them on a decline bench or a swiss ball.

Also try a resisted breathing crunch: Perform a regular crunch, but at the top of the crunch (i.e. when you’re curled up), inhale and exhale deeply and forcefully several times, without losing the “crunch”. Then, again, uncurl slowly.

Ball tosses are fun if you have a partner and a medicine ball (you can make your own by filling an old soccer ball or basketball with sand). For a beginner this is also fine with a regular unweighted

ball. Lie on your back holding ball. Partner stands at your feet. Stretch arms out so that they point towards the ceiling. Making sure upper body moves as one unit, crunch up, and as you come up to the top, throw the ball to your partner. They quickly toss it back. You don’t roll back down until you get the ball tossed back to you, then you uncurl and descend. Quickly rebound off the floor and crunch up again. The quick rebound is killer.

Hanging leg lifts done the old fashioned way are a good challenge. Hang from a chinup bar. Raise knees to chest, focusing not so much on the knee lift, but on slowly curling the spine up. To add resistance, hold a plate between your knees.

Use the cable stack for resistance to do cable crunches. Remember to make the upper body move

as one unit, and focus on pulling bellybutton to your spine. I actually do these facing away from the stack, but maybe I’m weird that way. You can also do these standing.

the barbell rollout

OK, here’s my all time favourite ab exercise. When I first learned this one, I did it every day because I thought it was so much fun. I managed to pull something in my obliques as a result and spent a few days shuffling around like someone who’d just given birth to octuplets. So don’t do them every day at first, umkay?

|

|

|

Load a bar on the floor with 25 lb plates, as shown. Bend over and grab it with a shoulder width grip. Come up on your toes. This is your starting position, as shown in the pic on the left.

Keeping your hands under your shoulders, as if you were doing a pushup on the bar (don’t let hands travel in front of your shoulders), roll the bar forward until your body is fully extended, as shown in the pic on the right. Notice that you are on the tips of your toes at this point.

Now the fun part! Drive hips up toward the ceiling (don’t think about pulling the barbell back, just think about folding the body in half). The barbell will roll back towards your feet. Return to starting position of the first pic. Repeat as desired.

Initially it helps to have someone sit in front of you and give the barbell a little push when you begin the return. Once you get the hang of it, it gets easier. To add difficulty, add weight to the bar and/or bungee cords to the bar, attached to something in front of you, so that as you roll back the bands stretch out.

what about my obliques?

Ah, an excellent question. The obliques, like the rectus abdominis, are likewise thin sheets of muscle which are both prime movers (in twisting and bending motions) and stabilizers. There are both internal and external obliques, and their fibres run crosswise to one another, like guy wires. Isn’t engineering wonderful? Strong obliques are also helpful in keeping the torso rigid while performing activities like squats.

If you’re performing compound free weight exercises, especially standing ones, there’s not much of a need to do direct oblique work. However, if you decide that you would like some, there are a couple of ways to do it.

Side bending oblique movements

Side bending motions are probably the easiest to learn and do.

While standing, hold a dumbbell in your right hand. Bend slowly sideways, from the waist, to the right so that the dumbbell travels down your leg. Get to a comfortable point of stretch. That’s your starting point.

Hooray! Saxon sidebends are fun!

Then, keeping your arms relaxed, unbend and keep moving to the left, bending over on the other side. Think about your left hand travelling down your leg and reaching for your knee. Unbend and come back to vertical. That’s one rep.

Repeat as desired, then switch sides. You can also use a barbell, or a cable handle set at the low position, instead of a dumbbell. By the way, a little helpful physics: this isn’t going to work as well with dumbbells in both hands, as I’ve seen some science dropouts doing.

An exercise which nicely trains both stability and side bending is the one-hand deadlift, aka the suitcase deadlift. You can do it just as a deadlift, if you’re training stability, or throw in a side bend as well if you’d like a bit of extra work. It’s quite simple: Set a weight down beside you, then squat down and pick it up like a suitcase. If you like, take it for a little walk while you’re at it.

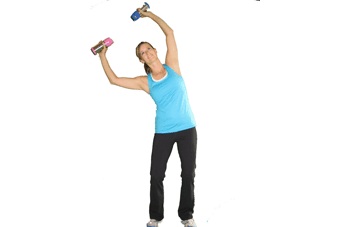

Saxon side bends are a fun challenge. Start standing tall, holding a weight overhead. Then carefully tip to one side or the other. I prefer to use a single dumbbell, and just put one hand on each end of it. You can also use a bar if you’re badass. But start light.

Torso rotation and anti-rotation movements

One of the under-appreciated functions of the torso musculature is anti-rotation — in other words, the ability to keep the torso from flapping all over the place when rotational or asymmetrical force is applied.

Examples of that include:

- controlling a punch or a throw

- controlling the torso when we are yanked off balance, as in a judo throw

- keeping the torso upright and controlled when we are carrying asymmetrical loads

- controlling pelvic and ribcage movement while running (and the arms and legs are swinging)

Now, there are two general types of twisting movements — one I recommend, and one I don’t.

- twisting from the waist — your pelvis and ribcage go in separate directions (not recommended)

- twisting using the torso as an integrated “block” from shoulder to hips (recommended)

When you twist using the torso as an integrated “block”, you also get the benefit of assistance from powerful leg and hip muscles. Remember that the body likes to move as a coherent unit, so unless you have a specific rehab need, it’s generally better to use complex movement “chains” rather than isolation movements. Sense in to what your body is doing as you perform these, and notice how you feel much stronger and more stable when you allow your hips and shoulders to get involved, and when you move your torso as a rigid and stable “block”.

You can do twisting/rotation motions three ways:

- across the body horizontally (like hitting a ball with a bat)

- across the body from bottom to top (like a golf swing), and

- across the body from top to bottom (like a wood chop).

Think of these three types of movements as making an asterisk — side to side; diagonally low to high across the body; and diagonally high to low across the body.

Cables or resistance bands are great for this; if you want to make these more explosive, try sideways medicine ball throws.

Try Googling “landmine twist” or “full contact twist” to see a classic movement done with an up-ended barbell, with one end of the barbell tucked into a corner.

A Pallof press is a nice example of an anti-rotation exercise. Even the humble yoga plank will do quite nicely.

when do i do all this stuff?

As I’ve mentioned, many folks do too high a volume of ab work at too low an intensity. You don’t really need more than a few sets per workout; shoot for something like 10-20 reps per set (or if you’re using a static hold such as a plank or Pallof press, try 30-60 sec).

Put your heavy ab training at the end of your workout so that you don’t fatigue the midsection too early and compromise torso stability (though you can use lighter ab work, such as standing pelvic tilts, as a warmup for something like squatting).

These are general guidelines, of course, and you can adjust them to suit your needs. But bear in mind that as always, more isn’t better, better is better!